Stepan Bandera

| Stepan Bandera Степан Бандера |

|

Stepan Bandera |

|

|

|

|

| Born | 1 January 1909 Uhryniv Staryi, Galiсia, Austria–Hungary |

|---|---|

| Died | 15 October 1959 (aged 50) Munich, West Germany |

| Nationality | Ukrainian |

| Occupation | Politician |

Stepan Andriyovych Bandera (Ukrainian: Степан Андрійович Бандера) (1 January 1909 – 15 October 1959) was a Ukrainian politician and one of the leaders of Ukrainian national movement in (Galicia) Western Ukraine, who headed the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). The son of a clerical family, Bandera was an activist, a scout, and eventually the leader of the Ukrainian Nationalist movement.

During his political career, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalist (OUN) split into two factions: the OUN-M and the OUN-B. Stepan Bandera was responsible for the proclamation of an Independent Ukrainian State in Lviv on 30 June 1941.

Soviet authorities authorised his assassination by the KGB in Munich, West Germany, on 15 October 1959.

Bandera is a controversial figure in contemporary Ukraine due to his proven and active cooperation with Nazi Germany in 1939-1941. In September 1941 Bandera was imprisoned by the Nazis; in September 1944 he was released.[1][2] Assessments have ranged from totally apologetic to sharply negative.[3] On 22 January 2010, the outgoing President of Ukraine Viktor Yushchenko awarded to Bandera the title of Hero of Ukraine (posthumously).[4] The award was rendered illegal by court on April 02, 2010. Three days later the Constitutional Court of Ukraine refused to start constitutional proceedings on the constitutionality of the Presidential decree Bandera's award was based on.[5] Although the Bandera family had been officially informed of the Donetsk's court ruling it has received no formal request by President Yanukovych to return the award.[6]

Contents |

Biography

Early life

Born in the village of Uhryniv Staryi, in the Kalush District of Galiсia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in now Western Ukraine. His father, Andriy Bandera, was the Greek-Catholic rite parish priest of Uhryniv Staryi. His mother, Myroslava, was also from an established clerical family, the daughter of a Greek-Catholic priest in Uhryniv Staryi.

Stepan spent his childhood in Uhryniv Staryi, in the house of his parents and grandparents.

In the spring of 1922, his mother died from tuberculosis of the throat.

Education

Bandera attended the Fourth Form Grammar School in Stryi,[7] where he also participated in sporting activities with the Sokil sports Society.

In 1923, at the age of 14, Bandera joined the Ukrainian scout organization "Plast" (Ukrainian: Пласт). Later in his association with Plast, he became a member of the group Chornomortsi (Black Sea Sailors).

Bandera received an unconfirmed 4 reprimands during his time as a yunak, and is still considered an ideal Plast member{fact}.

After graduation from high school in 1927, he planned to attend the Ukrainian College of Technology and Economics in Podebrady in Czechoslovakia, but was not granted a travel papers by the Polish authorities.[8]

In 1928, Bandera enrolled in the agronomy program at the Lviv Polytechnical Institute.[9] This was one of the few programs open to Ukrainians at the time.[7]

In both high school and University, Bandera was an active member of a number political groups with a nationalist agenda. One of the most active of these groups was the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, the OUN (Ukrainian: Організація Українських Націоналістів).

Political activism

Early Activities

Stepan Bandera had met and associated himself with members of a variety of Ukrainian nationalist organizations throughout his schooling - from Plast, to the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (Ukrainian: Українська Визвольна Організація) and also the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, the OUN (Ukrainian: Організація Українських Націоналістів). The most active of these organizations was the OUN, and the leader of the OUN was Andriy Melnyk.[7]

Because of his determined personality, Stepan Bandera quickly rose through the ranks of these organizations, becoming the chief propaganda officer of the OUN in 1931, the second in command of OUN in Galicia in 1932-33, and the head of the National Executive or the OUN in 1933.[9]

For Bandera, an inclusive policy of nation building was important - therefore, he focused on growing support amongst all classes of Ukrainians in Western parts of Ukraine. In the early 1930s, Bandera was very active in finding and developing groups of Ukrainian nationalists in both Western and Eastern Ukraine.[7]

OUN

Stefan Bandera became head of the OUN national executive in Galicia in June 1933. He expanded the OUN's network in Western Ukraine, directing it against both Poland and the Soviet Union. To stop expropriations, Bandera turned OUN against the Polish officials who were directly responsible for anti-Ukrainian policies. Activities included mass campaigns against Polish tobacco and alcohol monopolies and against the denationalization of Ukrainian youth. He was arrested in Lviv in 1934, and tried twice: first, concerning involvement in a plot to assassinate the minister of internal affairs, Bronisław Pieracki, and second at a general trial of OUN executives. He was sentenced to death.[9]

The death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.[9] He was held in Wronki Prison; in 1938 some of his followers tried unsuccessfully to break him out of the jail.[10]

According to various sources, Bandera was freed in September 1939, either by Ukrainian jailers after Polish jail administration left the jail,[11] by Poles[12] or by Germans.[13][14]

Soon thereafter Eastern Poland fell under Soviet occupation. Upon release from prison, Bandera moved to Krakow, the capital of the Germany's occupational General Government. There, he came in contact with the leader of the OUN, Andriy Melnyk. In 1940, the differences between the opinions of the two leaders were strained and the OUN split into two factions - the Melnyk faction led by Andriy Melnyk, which preached a more conservative approach to nation-building, (also known as the OUN-M), and the Bandera faction led by S. Bandera, which supported a revolutionary approach, (also known as the OUN-B).[15]

OUN(B) sought support in Germany's military circles, while the OUN(M) sought connections with its ruling clique. In November 1939 about 800 Ukrainian nationalists began training in Abwehr's military camps. In the first days of December, Bandera, without co-ordination with Melnyk, sent a courier to Lviv with directives for preparation of an armed uprising. The courier was intercepted by the NKVD, which had captured some of the OUN(M)'s leaders. Another such attempt was prevented in Autumn 1940.

Formation of Mobile Groups

Before the independence proclamation of 30 June 1941, Bandera oversaw the formation of so-called "Mobile Groups" (Ukrainian: мобільні групи) which were small (5-15 members) groups of OUN-B members who would travel from General Government to Western Ukraine and after German advance to Eastern Ukraine to encourage support for the OUN-B and establishing the local authorities ruled by OUN-B activists.[16] This included out pamphlets and growing membership in OUN.

In total, approximately 7,000 people participated in these mobile groups, and they found followers among a wide circle of intellectuals, such as Ivan Bahriany, Vasyl Barka, Hryhorii Vashchenko, and many others.[17]

Formation of the UPA

Relationship with Nazi Germany

The intermittently close relationship between Bandera, the OUN and Nazi Germany have been described by historians such as David Marples as "ambivalent", tactical and opportunistic, with both sides trying to exploit the other unsuccessfully.[18]

Prior to Operation Barbarossa, the OUN actively cooperated with Nazi Germany. According to the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and other sources, Bandera held meetings with the heads of Germany's intelligence, regarding the formation of "Nachtigall" and "Roland" Battalions. In spring the OUN received 2.5 million marks for subversive activities inside the USSR.[16][19][20].

On June 30, 1941, with the arrival of Nazi troops in Ukraine, Bandera and the OUN-B declared an independent Ukrainian State. Some of the published proclamations of the formation of this state that it "will work closely with the National-Socialist Greater Germany, under the leadership of its leader Adolf Hitler which is forming a new order in Europe and the world" - as stated in the text of the "Act of Proclamation of Ukrainian Statehood".[16][20].

On July 5, Bandera was arrested and transferred to Berlin. On July 12, the president of the newly-formed Ukrainian state, Yaroslav Stetsko, was also arrested and taken to Berlin. Although released from custody on July 14, both were required to stay in Berlin. In 1941 relations between Nazi Germany and the OUN-B soured to the point where a Nazi document dated 25 November 1941 stated that "... the Bandera Movement is preparing a revolt in the Reichskommissariat which has as its ultimate aim the establishment of an independent Ukraine. All functionaries of the Bandera Movement must be arrested at once and, after thorough interrogation, are to be liquidated...".[21] Military oppression of the population increased, and it soon became evident that military action against Nazi Germany was necessary. Meetings of the OUN leadership held February 1943 led the creation of the military wing of the OUN-B, which was the Ukrainian Insurgent Army.

In January 1942, transferred to Sachsenhausen concentration camp's special barrack for high profile political prisoners Zellenbau.[22]

In 1943, Bandera was asked by Nazi officers whether he would support Hitler or not. According to one unverified source, "Bandera quickly replied that it was clear that the Nazis would lose the war, and there was nothing to be gained for Ukraine by siding with them".[23]

In September 1944 [1] Bandera was released by [the German authorities] in the hope that he would rouse the native populace to fight the advancing Soviet Army. With German consent Bandera set up headquarters in Berlin.[2] Germans supplied OUN-B and UIA by air with arms and equipment. Assigned German personnel and agents trained to conduct terrorist and intelligence activities behind Soviet lines, as well as some OUN-B leaders, were also transported by air until early 1945.[24][25]

According to the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and other sources, Bandera had meetings with the heads of Germany's intelligence, regarding the formation of "Nachtigall" and "Roland" Battalions. In spring the OUN received 2.5 million marks for subversive activities inside the USSR.[16][19][20] 29 June 1941 Bandera was removed from Lviv and travelled to Krakow without permission from the German authorities.[26] On 30 June 1941, OUN(B) declared in Lviv the formation of a Ukrainian state. Some of the published proclamations of the formation of this state that it "will work closely with the National-Socialist Greater Germany, under the leadership of its leader Adolf Hitler which is forming a new order in Europe and the world" - as stated in the text of the "Act of Proclamation of Ukrainian Statehood".[16][20] Gestapo and Abwehr officials protected Bandera followers, as both organizations intended to use them for their own purposes.[27] On July 5, Bandera was placed under honorary arrest (Latin: custodia honesta) in Krakow, and transported to Berlin the next day. 14 July he was released, but required to stay in Berlin. 12 July 1941 he was joined in Berlin by his deputy Yaroslav Stetsko, whom the Germans had moved from Lviv after an unsuccessful attempt by unknown persons to assassinate him.[28] During July–August both of them submitted dozens of proposals for cooperation to different Nazi institutions (OKW, RSHA etc.) [29] Although German officials demanded that he stop his armed activities against Melnyks OUN and recall the "Act of June the 30th, 1941", he refused.

After the German troops crossed the Dnieper River in September 1941, Hitler decided there was no need to establish a Ukrainian state.[16][20] After the assassination of two key members of OUN-M, said to have been committed by members of OUN-B, Bandera and Stetsko on 15 September 1941 were held in the central Berlin prison at Spandau and, in January 1942, transferred to Sachsenhausen concentration camp's special barrack for high profile political prisoners Zellenbau.[22] In 1943, Bandera was asked by Nazi officers whether he would support Hitler or not. According to one unverified source, "Bandera quickly replied that it was clear that the Nazis would lose the war, and there was nothing to be gained for Ukraine by siding with them".[23]

In 1941 relations between Nazi Germany and the OUN-B deteriorated to the point where a Nazi document dated 25 November 1941 stated that "... the Bandera Movement is preparing a revolt in the Reichskommissariat which has as its ultimate aim the establishment of an independent Ukraine. All functionaries of the Bandera Movement must be arrested at once and, after thorough interrogation, are to be liquidated...".[21] Military oppression of the population increased, and it soon became evident that military action against Nazi Germany was necessary. Meetings of the OUN leadership held February 1943 led the creation of the military wing of the OUN-B, which was the Ukrainian Insurgent Army.

In April 1944 Bandera and his deputy Yaroslav Stetsko were approached by an RSHA official to discuss plans for diversions and sabotage against Soviet Army.[30]

In September 1944 [31] Bandera was released by [the German Authorities] in the hope that he would rouse the populace to fight the advancing Soviet Army. With German consent Bandera set up headquarters in Berlin.[2] Germans supplied OUN-B and UIA by air with arms and equipment. Assigned German personnel trained to conduct terrorist and intelligence activities behind Soviet lines, as well as some OUN-B leaders, were also transported by air until early 1945.[24][25]

Views towards other ethnic groups

Bandera and the Poles

In May 1941 at a meeting in Krakow the leadership of Bandera's OUN faction adopted the program "Struggle and action for OUN during the war" (Ukrainian: "Боротьба й діяльність ОУН під час війни») which outlined the plans for activities at the onset of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union and the western territories of the Ukrainian SSR.[32] Section G of that document –"Directives for first days of the organization of the living state" Ukrainian: "Вказівки на перші дні організації державного життя» outline activity of the Bandera followers during summer 1941 [33] In the subsection of "Minority Policy" the OUN-B ordered: "Moskali (a derogatory term for Russians), Poles, Jews are hostile to us must be exterminated in this struggle, especially those who would resist our regime: deport them to their own lands, importantly: destroy their intelligentsia"... ... "so-called Polish peasants must be assimilated"... "Destroy their leaders." In late 1942, Ukrainian nationalist groups were involved in a campaign of ethnic cleansing of Volhynia, and in early 1944, these campaigns began to include Eastern Galicia. It is alleged that up to 100,000 Polish civilians were murdered, by Ukrainian groups including the OUN-Bandera which bears primary responsibility for the massacres.[34]

Bandera and antisemitism

Unlike competing Polish, Russian, Hungarian or Romanian nationalisms in late imperial Austria, imperial Russia, interwar Poland and Romania, Ukrainian nationalism did not include antisemitism as a core aspect of its program and saw Russians as well as Poles as the chief enemy with Jews playing a secondary role.[35] Nevertheless, Ukrainian nationalism was not immune to the influence of the antisemitic climate in the Eastern and Central Europe,[35] had already become highly racialized in the late 19th century, and had developed an elaborate anti-Jewish discourse.[36]

The predominance of the Russians, rather than the Jewish minority, as the principal perceived enemy of Ukrainian nationalists was highlighted at the OUN-B's Conference in Krakow in 1941 when it declared that "The Jews in the USSR constitute the most faithful support of the ruling Bolshevik regime, and the vanguard of Muscovite imperialism in Ukraine. The Muscovite-Bolshevik government exploits the anti-Jewish sentiments of the Ukrainian masses to divert their attention from the true cause of their misfortune and to channel them in a time of frustration into pogroms on Jews. The OUN combats the Jews as the prop of the Muscovite-Bolshevik regime and simultaneously it renders the masses conscious of the fact that the principal foe is Moscow."[37] In May 1941 at a meeting in Krakow the leadership of Bandera's OUN faction adopted the program "Struggle and action of OUN during the war" (Ukrainian: "Боротьба й діяльність ОУН під час війни») which outlined the plans for activities at the onset of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union and the western territories of the Ukrainian SSR.[38] Section G of that document –"Directives for first days of the organization of the living state" Ukrainian: "Вказівки на перші дні організації державного життя» outline activity of the Bandera followers during summer 1941 [39] In the subsection of "Minority Policy" the OUN-B ordered: "Moskali (a derogatory terms for Russians), Poles, Jews are hostile to us must be exterminated in this struggle, especially those who would resist our regime: deport them to their own lands, importantly: destroy their intelligentsia that may be in the positions of power ... Jews must be isolated, removed from governmental positions in order to prevent sabotage, those who are deemed necessary may only work with an overseer... Jewish assimilation is not possible." [40][41][42] Later in June Yaroslav Stetsko sent to Bandera a report in which he indicated - "We are creating a militia which would help to get remove the Jews and protect the population." [43][44] Leaflets spread in the name of Bandera in the same year called for the "destruction" of ""Moscow", Poles , Hungarians and Jewry.[45][46][47] In 1941-1942 while Bandera was cooperating with the Germans, OUN members did take part in anti-Jewish actions.

In 1942 German intelligence concluded that Ukrainian nationalists were indifferent to the plight of the Jews and were willing to either kill them or help them, depending on what better served their cause. Several Jews took part in Bandera's underground movement,[48] including one of Bandera's close associates Richard Yary who was also married to a Jewish woman. Another notable Jewish UPA member was Leyba-Itzik "Valeriy" Dombrovsky. According to a report to the Chief of the Security Police in Berlin dated March 30, 1942, "...it has been clearly established that the Bandera movement provided forged passports not only for its own members, but also for Jews.".[49] The false papers were most likely supplied to Jewish doctors or skilled workers who could be useful for the movement.[50]

When Bandera was in conflict with the Germans, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army under his authority sheltered many Jews.[51] and included Jewish fighters and medical personnel.[52][53] In the official organ of the OUN-B's leadership, instructions to OUN groups urged those groups to "liquidate the manifestations of harmful foreign influence, particularly the German racist concepts and practices." [54] In summary, Bandera's movement sometimes harmed and sometimes helped Jews depending on particular circumstances and on Bandera's relationship with Germany.

Death

On 15 October 1959, Stepan Bandera collapsed outside of Kreittmayrstrasse 7 in Munich and died shortly thereafter. A medical examination established that the cause of his death was poison (cyanide gas[55]). On October 20, 1959 Stepan Bandera was buried in the Waldfriedhof Cemetery in Munich.

Two years later, on 17 November 1961, the German judicial bodies announced that Bandera's murderer had been a KGB defector Bohdan Stashynsky who acted on the orders of Soviet KGB head Alexander Shelepin and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev.[56] After a detailed investigation against Stashynskyi, a trial took place from 8 October to 15 October 1962. The sentence was handed down on 19 October in which Stashynskyi was sentenced to 8 years imprisonment. The Federal Court of Justice of Germany confirmed at Karlsruhe that in the Bandera murder, the Soviet secret service was the main guilty party.

Family

His brother Oleksandr (who had a PhD in Political Economy from the University of Rome) and brother Vasyl (a graduate in Philosophy, Lviv University) were arrested and interned in Auschwitz, where they were allegedly killed by Polish inmates in 1942.[57]

Andriy Bandera, Stepan's father was arrested in late May 1941 for harbouring an OUN member and transferred to Kiev. In 8 July he was sentenced to death and executed on the 10th. His sisters Oksana and Marta-Maria were arrested by the NKVD in 1941 and sent to GULAG in Siberia. Both were released in 1960 without the right to return to Ukraine. Marta-Maria died in Siberia in 1982, and Oksana returned to Ukraine in 1989 where she died in 2004. Another sister, Volodymyra - was sentenced to a term in Soviet labour camps from 1946-1956. She returned to Ukraine in 1956.[58] Stepan's brother Bohdan's fate remains unknown, as accounts vary: some sources say he was killed by the Gestapo in Mykolayiv in 1943, other sources say he was killed by the NKVD operatives in 1944, but to date even the family members have no definite information.

Legacy

The Soviet Union actively campaigned to discredit Bandera and all other Ukrainian nationalist partisans of World War II.[59][60][61][62]

In an interview with Russian newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda in 2005 former KGB Chief Vladimir Kryuchkov claimed that "the murder of Stepan Bandera was one of the last cases when the KGB disposed of undesired people by means of violence."[63]

In late 2006 the Lviv city administration announced the future transference of the tombs of Stepan Bandera, Andriy Melnyk, Yevhen Konovalets and other key leaders of OUN/UPA to a new area of Lychakivskiy Cemetery specifically dedicated to Ukrainian national liberation struggle.[64]

In October 2007, the city of Lviv erected a statue dedicated to the OUN and UPA leader Stepan Bandera.[65] The appearance of the statue has engendered a far-reaching debate about the role of Stepan Bandera and UPA in Ukrainian History. The two previously erected statues were blown up by unknown perpetrators, the current is guarded by a militia detachment 24/7. On October 18, 2007, the Lviv City Council adopted a resolution establishing the "Award of Stepan Bandera."[66][67]

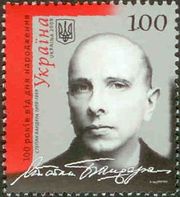

On January 1, 2009 his 100th birthday was celebrated in several Ukrainian centres[68][69][70][71][72] and an postal stamp with his portrait was issued the same day.[73]

Hero of Ukraine Award

On January 22, 2010, on the Day of Unity of Ukraine, the then-President of Ukraine Viktor Yushchenko awarded to Bandera the title of Hero of Ukraine (posthumously). The Hero of Ukraine award is a extension of the traditional Soviet idolization that was reestablished by the former president Leonid Kuchma in 1998. A grandson of Bandera, also named Stepan, accepted the award that day from the Ukrainian President during the state ceremony to commemorate the Day of Unity of Ukraine at the National Opera House of Ukraine.[74][75][76][77] This award has been condemned by the Simon Wiesenthal Center[78] and the Student Union of French Jews.[79] On the very same day numerous Ukrainian media, particularly such as the pro-Russian Segonia, published dishonoring articles in that regard mentioning cases of some former Soviet spies (Yevhen Berezniak) wishing to dump their Hero of Ukraine title.[80] On the other hand the decree was applauded by Ukrainian nationalists, in Western Ukraine and by a small portion of the Ukrainian-Americans.[81][82]

On January 25, 2010 Head of the Czech Confederation political prisoners Nadia Kavalirova expressed support for the decision of the Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko to award the title of Hero of Ukraine to Stepan Bandera.

It is good that he (Yushchenko) made this step, many Czech politicians can draw lessons from it, - said N.Kavalirova.

While the representatives from several antifascist organizations in the neighboring Slovakia condemned the award to Bandera, calling the decision of Yushchenko a provocation was reported by the RosBisnessConsulting referring to the Radio Praha.[83]

On February 9, 2010 the Poland's Senate Marshal Bogdan Borusewicz said at a meeting with the head of Russia's Federation Council Sergei Mironov, that adaptation of the Hero title of Ukraine to Bandera is an internal matter of the Ukrainian government.[84]

On February 25, 2010 the European Parliament criticized the decision by then ex-president of Ukraine Yushchenko to award Bandera the title of Hero of Ukraine and expressed hope it would be reconsidered.[85]

On March 3, 2010 the Ivano-Frankivsk regional council called on the European Parliament to review this resolution.[86]

Taras Kuzio, a senior fellow in the chair of Ukrainian studies at the University of Toronto has suggested Yushchenko awarded Bandera the award in order to frustrate Yulia Tymoshenko's changes to get elected President during the Ukrainian Presidential elections 2010.[87]

President Viktor Yanukovych stated on March 5, 2010 he would make a decision to repeal the decrees to honour the tittle as Heroes of Ukraine to Bandera and fellow nationalist Roman Shukhevych before the next Victory Day.[88] Although the Hero of Ukraine decrees do not stipulate the possibility that a decree on awarding this title can be annulled.[89]

On April 2, 2010, an administrative Donetsk region court ruled the Presidential decree awarding the title to be illegal. According to the court's decision, Bandera wasn't a citizen of the Ukrainian SSR (vis-à-vis Ukraine).[90][91]

Stepan Bandera, grandson of Ostap Bandera and journalist, argued that a year before Roman Shukhevych's Hero of Ukraine award was also challenged in the same court. And that time the court had ruled that Shukhevych's Hero of Ukraine award did not contravene Ukrainian law. Just like Bandera Shukhevych was born in Austria–Hungary.[92]

On April 5, 2010 the Constitutional Court of Ukraine refused to start constitutional proceedings on the constitutionality of the President Yushchenko decree the award was based on. A ruling by the court was submissioned by the Supreme Council of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea on January 20, 2010.[5]

According to grandson, Stepan Bandera, although the Bandera family has been officially informed of the Donetsk's court ruling it still is not asked by President Yanukovych to return the award.[6]

On April 23, 2010 in the program Velyka Polityka with Yevgeniy Kiseliov on the television channel Inter, the Ukrainian Minister of Justice Oleksandr Lavrynovych declared his jurisprudential point in regards to the circumstances of establishing the award, while responding to questions on the cancellation of presidential orders by the Donetsk Administration District Court (on April 21) for establishing the Ukrainian Hero titles for Stepan Bandera and Roman Shukhevych:[93]

| “ | If the head of state wants to award a historical personality with the title of Hero of His country, in that case, he cares not about those individuals, but rather about himself. And here, if our debate today goes about a corruption, I can say that this is one of the varieties of corrupted activities. For, if the active President wants to cling to achievements, to popularization, to honoring of a historical figure in the society, what purpose, I wonder, does the man not assigning the title of Hero of Ukraine to Volodymyr the Great, Yaroslav the Wise, Taras Shevchenko? Why are they being offended? Why Lesia Ukrainka, Ivan Franko are not awarded? . | ” |

In clarification reply that while for all the chances to do such a thing has the current President Viktor Yanukovych, the Minister of Justice put a weight on the fact that it should be approached from such perspective that heroes of previous generations do not require official decisions of those presidents who "cannot level with them, who in such way want to join the glory of those personalities who have created the history of their state".

On April 25, 2010 the Russian-speaking newspaper in Ukraine "Focus" stated that the reason for denying the establishment of such award was the fact that both Shukhevych and Bandera were not citizens of Ukraine.[94]

On May 14, 2010 in the statement of the Russian Foreign Ministry was said about the award: "that the event is so odious that it could no doubt cause a negative reaction in the first place in Ukraine. Already it is known a position on this issue of a number of Ukrainian politicians, who believe that solutions this kind do not contribute to the consolidation of Ukrainian public opinion".[95]

Honorary citizen titles

- Honorary citizen of Nadvirna[96]

- Honorary citizen of Khust (March 10, 2010)[2]

- Honorary citizen of Ternopil (April 30, 2010)[3]

- Honorary citizen of Ivano-Frankivsk (May 6, 2010)[4]

- Honorary citizen of Lviv (May 7, 2010)[5]

Monuments

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Staryi Uhryniv

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Lviv

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Ternopil

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Ivano-Frankivsk

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Kolomyia

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Kozivka

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Drohobych

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Dubliany

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Terebovlya

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Berezhany

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Boryslav

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Buchach

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Mykytyntsi

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Mostyska

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Sambir

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Stryi

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Zalishchyky

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Chervonohrad

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Verbiv

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Horodenka

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Hrabivka

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Seredniy Bereziv

- Monument of Stepan Bandera in Strusiv

Museums

- Museum of Stepan Bandera in Dubliany

- Museum of Stepan Bandera in Volya-Zaderevatska

- Museum of Stepan Bandera in Staryi Uhryniv

- Museum of Stepan Bandera in Yahilnytsya

- Museum of liberation struggle named after Stepan Bandera in London

Streets

- Stepan Bandera street in Lviv

- Stepan Bandera street in Lutsk (former Suvorovska street)

- Stepan Bandera street in Rivne (former Moskovska street)

- Stepan Bandera street in Kolomyia

- Stepan Bandera prospect in Ternopil

- Stepan Bandera street in Ivano-Frankivsk

- Stepan Bandera street in Chervonohrad

- Stepan Bandera street in Drohobych (former Slyusarska street)

- Stepan Bandera street in Stryi

- Stepan Bandera street in Kalush

- Stepan Bandera street in Kovel

- Stepan Bandera street in Volodymyr-Volynskyi

- Stepan Bandera street in Horodenka

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 БАНДЕРА Степан Андрійович at Institute of History - National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 WEST GERMANY: The Partisan Monday, Nov. 02, 1959

- ↑ Довкола цієї контраверсійної постаті й донині точаться гострі суперечки, що супроводжуються розмаїттям оцінок: від різко негативних до суцільно апологетичних. D.Vyedeneyev O.Lysenko OUN and foreign intelligence services 1920s-1950s Ukrainian Historical Magazine 3, 2009 p.132– Institute of History National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine http://www.history.org.ua/JournALL/journal/2009/3/11.pdf

- ↑

United Kingdom УКАЗ ПРЕЗИДЕНТА УКРАИНЫ № 46/2010: О присвоении С.Бандере звания Герой Украины. President of Ukraine. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

United Kingdom УКАЗ ПРЕЗИДЕНТА УКРАИНЫ № 46/2010: О присвоении С.Бандере звания Герой Украины. President of Ukraine. Retrieved January 22, 2010. - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Constitutional Court refuses to consider case on Bandera's title of Hero of Ukraine, Kyiv Post (April 12, 2010)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Analysis: Ukraine leader struggles to handle Bandera legacy, Kyiv Post (April 14, 2010)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "Murdered by Moscow. - [4] Stepan Bandera, His Life and Struggle (by Danylo Chaykovsky)". Exlibris.org.ua. http://exlibris.org.ua/murders/r04.html. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ↑ Ukrainian College of Technology and Economics in Podebrady

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "Bandera, Stepan". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/pages/B/A/BanderaStepan.htm. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ↑ (Polish) Janusz Marciszewski, Uwolnić Banderę, NaszeMiasto.pl

- ↑ http://kray.ridne.net/bandera

- ↑ T. Snyder, Causes of Ukrainian Polish ethnic cleansing, Past&Present, nr 179, p. 205

- ↑ Anna Reid, Borderland: a journey through the history of Ukraine, Phoenix, 2002, p. 158

- ↑ S. Karnautska, Portret bez retushi, L'vovs'kaya pravda, 8 May 1991, p. 2

- ↑ "Ukraine :: World War II and its aftermath - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/612921/Ukraine/30082/World-War-II-and-its-aftermath#ref=ref404610. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 ОУН в 1941 році: документи: В 2-х ч Ін-т історії України НАН України К. 2006 ISBN 966-02-2535-0

- ↑ By Sviatoslav LYPOVETSKY. "Eight decades of struggle /ДЕНЬ/". Day.kiev.ua. http://www.day.kiev.ua/264657/. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ↑ David Marples. (2007). Heroes and villains: creating national history in contemporary Ukraine . Central European University Press, pp. 150 and 161

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Організація українських націоналістів і Українська повстанська армія. Інститут історії НАН України.2004р Організація українських націоналістів і Українська повстанська армія, Раздел 1 http://www.history.org.ua/LiberUA/Book/Upa/1.pdf стр. 17-30

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 І.К. Патриляк. Військова діяльність ОУН(Б) у 1940—1942 роках. — Університет імені Шевченко \Ін-т історії України НАН України Київ, 2004 (No ISBN)

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Ukrainian History - World War II in Ukraine". InfoUkes. http://www.infoukes.com/history/ww2/page-08.html. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Berkhoff, K.C. and M. Carynnyk 'The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and Its Attitude toward Germans and Jews: Iaroslav Stets'ko's 1941 Zhyttiepys' in: Harvard Ukrainian Studies, vol. 23 (1999), nr. 3/4, pp. 149—184 .

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 M.Logusz "The Waffen-SS 14th Grenadier Division, 1943-1945". Atglen, PA: Schiffer Military History, 1997 558 p. illus. (Schiffer, 4880 Lower Valley Rd. Atglen PA 19310, FAX: (610) 593-2002

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, p.338

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 D.Vyedeneyev O.Lysenko OUN and foreign intelligence services 1920s-1950s Ukrainian Historical Magazine 3, 2009 p.137– Institute of History National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine http://www.history.org.ua/JournALL/journal/2009/3/11.pdf

- ↑ p.420 ОУН в 1941 році: документи: В 2-х ч Ін-т історії України НАН України К. 2006 ISBN 966-02-2535-0

- ↑ p.15 ОУН в 1941 році: документи: В 2-х ч Ін-т історії України НАН України К. 2006 ISBN 966-02-2535-0 - У владних структурах рейху знайшлися сили яки з прагматичних міркувань стали на захист бандерівців. Керівники гестапо сподівалися використовувати їх у власних цілях а керівники абверу а радянському тилу.

- ↑ Після проголошення держави й уряду наложили на нього дня 5.7. почесний арешт (Еренгафт) та перевезли його до Берліна. Дня 14.7 провідника організації звільнено із забороною опускати Берлін. p.420 ОУН в 1941 році: документи: В 2-х ч Ін-т історії України НАН України К. 2006 ISBN 966-02-2535-0

- ↑ p.16 Голова уряду Я.Стецько майже до кінця серпня вільно проживав у Берліні і закидав посланнями відомства Розенберга, Ріббентропа,Гіммлера і Кейтеля) ОУН в 1941 році: документи: В 2-х ч Ін-т історії України НАН України К. 2006 ISBN 966-02-2535-0

- ↑ Завдання підривної діяльності проти Червоної армії обговорювалося на нараді під Берліном у квітні того ж року (1944) між керівником таємних операцій вермахту О.Скорцені й лідерами українських націоналістів С.бандерою та Я.Стецьком» D.Vyedeneyev O.Lysenko OUN and foreign intelligence services 1920s-1950s Ukrainian Historical Magazine 3, 2009 p.137– Institute of History National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine http://www.history.org.ua/JournALL/journal/2009/3/11.pdf

- ↑ БАНДЕРА Степан Андрійович at Institute of History - National Academy of Sciences of Ukrainehttp://www.history.org.ua/?l=EHU&verbvar=Bandera_S&abcvar=2&bbcvar=1

- ↑ І.К. Патриляк. Військова діяльність ОУН(Б) у 1940—1942 роках. — Університет імені Шевченко \Ін-т історії України НАН України Київ, 2004 (No ISBN p.111

- ↑ І.К. Патриляк. Військова діяльність ОУН(Б) у 1940—1942 роках. — Університет імені Шевченко \Ін-т історії України НАН України Київ, 2004 (No ISBN p.56 .

- ↑ Timothy Snyder, The Reconstruction of Nations, page 164. Books.google.com. 2006-03-22. http://books.google.com/books?id=xSpEynLxJ1MC&pg=PA164&dq=Roman+Shukhevych+Poles&sig=ACfU3U3VN6mYgaONrLtTsJpxyJtZqLaDTw#PPA164,M1. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Ukrainian Collaboration in the Extermination of the Jews during the Second World War: Sorting Out the Long-Term and Conjunctural Factors by John-Paul Himka, University of Alberta. Taken from The Fate of the European Jews, 1939-1945: Continuity or Contingency, ed. Jonathan Frankel (New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), Studies in Contemporary Jewry 13 (1997): 170-89.

- ↑ p.16 "War Criminality: A Blank Spot in the Collective Memory of the Ukrainian Diaspora." Spaces of Identity 5, no. 1 (April 2005) by John-Paul Himka, University of Alberta. http://www.archive.org/details/warCriminalityABlankSpotInTheCollectiveMemoryOfTheUkrainian

- ↑ Philip Friedman. Ukrainian-Jewish Relations During the Nazi Occupation. In Roads to Extinction: Essays on the Holocaust. (1980) New York: Conference of Jewish Social Studies. pp.179-180

- ↑ І.К. Патриляк. Військова діяльність ОУН(Б) у 1940—1942 роках. — Університет імені Шевченко \Ін-т історії України НАН України Київ, 2004 (No ISBN p.111

- ↑ І.К. Патриляк. Військова діяльність ОУН(Б) у 1940—1942 роках. — Університет імені Шевченко \Ін-т історії України НАН України Київ, 2004 (No ISBN p.56 .

- ↑ Меншинева політика. 16. Національні меншини поділяються на: а) приязні нам, себто членів досі поневолених народів; б) ворожі нам, москалі, поляки, жиди. а) Мають однакові права з українцями, уможливлюємо їм поворот в їхню батьківщину. б) Винищування в боротьбі, зокрема тих, що боронитимуть режиму: переселювання в їх землі, винищувати головно інтелігенцію, якої не вільно допускати до ніяких урядів, і взагалі унеможливлюємо продуку- вання інтелігенції, себто доступ до шкіл і т.д. Наприклад, так званих польських селян треба асимілювати, усвідомлюючи з місця їм, тим більше в цей гарячий, повний фанатизму час, що вони українці, тільки латинського обряду, насильно асимільовані. Проводирів нищити. Жидів ізолювати, поусувати з урядів, щоб уникнути саботажу, тим більше москалів і поляків. Коли б була непоборна потреба оставити, приміром, в господарськім апараті жида, поставити йому нашого міліціянта над головою і ліквідувати за найменші провини. Керівники поодиноких галузей життя можуть бути лише українці, а не чужині – вороги. Асиміляція жидів виключається. p.103-104 ОУН в 1941 році: документи: В 2-х ч Ін-т історії України НАН України К. 2006 ISBN 966-02-2535-0

- ↑ same text p.485-486 І.К. Патриляк. Військова діяльність ОУН(Б) у 1940—1942 роках. — Університет імені Шевченко \Ін-т історії України НАН України Київ, 2004

- ↑ Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, p.63

- ↑ Dr. Franziska Bruder "Radicalization of the Ukrainian Nationalist Policy in the context of the Holocaust" The International Institute for Holocaust Research No. 12 -June 2008 p.37 ISSN 1565-8643

- ↑ "робимо міліцію що поможе жидів усувати www.history.org.ua/LiberUA/Book/Upa/2.pdf Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, p.63 ]

- ↑ І.К. Патриляк. Військова діяльність ОУН(Б) у 1940—1942 роках. — Університет імені Шевченко \Ін-т історії України НАН України Київ, 2004 (No ISBN p 324 "Народе знай Москва Польша, мадяри жидова- це твої вороги. Нищ їх"

- ↑ same text p.259 July p 576 December - ОУН в 1941 році: документи: В 2-х ч Ін-т історії України НАН України К. 2006 ISBN 966-02-2535-0

- ↑ Harvest of despair: life and death in Ukraine under Nazi rule by Karel Cornelis Berkhoff (2004)

- ↑ Philip Friedman. Ukrainian-Jewish Relations During the Nazi Occupation. In Roads to Extinction: Essays on the Holocaust. (1980) New York: Conference of Jewish Social Studies. pg. 204

- ↑ By Herbert Romerstein. "Divide and Conquer: the KGB Disinformation Campaign Against Ukrainians and Jews. Ukrainian Quarterly, Fall 2004. By Herbert Romerstein". Iwp.edu. http://www.iwp.edu/news/newsID.139/news_detail.asp. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ↑ Richard Breitman. U.S Intelligence and the Nazis. Cambridge University Press. 2005. pg. 250

- ↑ Friedman, P.. Ukrainian-Jewish Relations During the Nazi Occupation, YIVO Annual of Jewish Social Science v. 12, pp. 259–96, 1958–59.

- ↑ Leo Heiman, "We Fought for Ukraine - The Story of Jews Within the UPA", Ukrainian Quarterly Spring 1964, pp.33-44.

- ↑ Philip Friedman. Ukrainian-Jewish Relations During the Nazi Occupation. In Roads to Extinction: Essays on the Holocaust. (1980) New York: Conference of Jewish Social Studies. pg. 204. Among several Jews saved by UPA Friedman mentions a Jewish physician and his wife whom he knows in Israel who were saved by UPA, another Jewish physician and his brother who lived in Tel Aviv after the war

- ↑ Philip Friedman. Ukrainian-Jewish Relations During the Nazi Occupation. In Roads to Extinction: Essays on the Holocaust. (1980) New York: Conference of Jewish Social Studies. pg. 188

- ↑ The Partisan, Time (magazine) (November 2, 1959)

- ↑ The Poison Pistol, TIME Magazine, December 01, 1961

- ↑ p.190 The Frankfurt Auschwitz trial, 1963-1965: genocide, history, and the limits Devin Owen Pendas Cambridge University Press [1]

- ↑ Бандерштадт: місто Бандер №4 (231) 28 січня 2010р. http://www.gk-press.if.ua/node/512 http://www.gk-press.if.ua/node/512

- ↑ Stepan Bandera: Hero or Nazi sympathizer?, Kyiv Post (October 2, 2008)

- ↑ Myths from U.S.S.R. still have strong pull today, Kyiv Post (February 25, 2009)

- ↑ US intelligence perceptions of Soviet power, 1921-1946 by Léonard Leshuk, Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0714653063/ISBN 978-0714653068 (page 229)

- ↑ Heroes and villains: creating national history in contemporary Ukraine by David R. Marples, Central European University Press, 2007, ISBN 9637326987/ISBN 978-9637326981 (page 234)

- ↑ Mosnews.com

- ↑ "Information website of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group". Khpg.org. http://www.khpg.org/en/index.php?id=1161553853. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ↑ Events by themes: Monument to Stepan Bandera in Lvov, UNIAN photo service (October 13, 2007)

- ↑ Design by Maxim Tkachuk, web-architecture by Volkova Dasha, templated by Alexey Kovtanets, programming by Irina Batvina, Maxim Bielushkin, Sergey Bogatyrchuk, Vitaliy Galkin, Victor Lushkin, Dmitry Medun, Igor Sitnikov, Vladimir Tarasov, Alexander Filippov, Sergei Koshelev, Yaroslav Ostapiuk. "Корреспондент » Украина » События » Львов основал журналистскую премию имени Бандеры". Korrespondent.net. http://www.korrespondent.net/main/212672/. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ↑ "Розпорядження №495". .city-adm.lviv.ua. http://www8.city-adm.lviv.ua/Pool%5CInfo%5Cdoclmr_1.NSF/(SearchForWeb)/C80E4FAD6E57B422C22573760056D927?OpenDocument. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- ↑ Events by themes: Celebration of 100 birth anniversary of Stepan Bandera in Zaporozhye (Zaporozhye), UNIAN photo service (January 1, 2009)

- ↑ Events by themes: Mass meeting, devoted to 100 birth anniversary of Stepan Bandera, in Stariy Ugriniv village, UNIAN photo service (January 1, 2009)

- ↑ Events by themes: Monument to Stepan Banderq and memorial complex the heroes of UPA were opened in Ivano-Frankivsk (Ivano-Frankivsk), UNIAN photo service (January 1, 2009)

- ↑ Events by themes: Kharkiv nationalists were disallowed to arrange a torchlight procession in honor of Bandera's birthday (Kharkiv), UNIAN photo service (January 1, 2009)

- ↑ Events by themes: Action "Stepan Bandera is a national hero" (Kiev), UNIAN photo service (January 1, 2009)

- ↑ 2009 Philatelic Issues - Stefan Bandera (1909-1959) The Ukrainian Electronic Stamp Album

- ↑ President Viktor Yushchenko awarded title Hero of Ukraine to OUN Head Stepan Bandera, Radio Ukraine (January 22, 2010)

- ↑ Stepan Bandera becomes Ukrainian hero, Kyiv Post (January 22, 2010)

- ↑ Events by themes: 91th anniversary of Collegiality of Ukraine, UNIAN (January 22, 2010)

- ↑ Ukraine. Rehabilitation and new heroes, EuropaRussia (January 29, 2010)

- ↑ WIESENTHAL CENTER BLASTS UKRAINIAN HONOR FOR NAZI COLLABORATOR, Simon Wiesenthal Center (January 28, 2010)

- ↑ (French) L'UEJF choquée par Ioutchenko, pour qui Bandera est un héros de l'Ukraine, UEJF, February 1, 2010

- ↑ Majot Vikhr by Vlad Bereznoi for Segodnia. January 22, 2010 (Russian)

- ↑ Analysis: Ukraine leader struggles to handle Bandera legacy, Kyiv Post (April 13, 2010)

- ↑ Ukrainians in New York take to streets to protest Russian fleet, Kyiv Post (May 6, 2010)

- ↑ Czech political prisoners approve the adaptation of the Bandera's Hero award (Ukrainian)

- ↑ [http://www.ukrpohliad.org/news.php/news/2331 Ukrainsky pohliad (Ukrainian view) February 9, 2010) (Ukrainian)

- ↑ European parliament hopes new Ukraine's leadership will reconsider decision to award Bandera title of hero, Kyiv Post (February 25, 2010)

- ↑ Ivano-Frankivsk regional council calls on European Parliament to review resolution on Bandera, Kyiv Post (March 3, 2010)

- ↑ Gender bias, anti-Semitism contributed to Yanukovych's victory, Kyiv Post (March 18, 2010)

- ↑ Yanukovych to strip nationalists of hero status, Kyiv Post (March 5, 2010)

- ↑ Party of Regions proposes legal move to strip Bandera of Hero of Ukraine title, Kyiv Post (February 17, 2010)

- ↑ Ukraine court strips Bandera of Hero of Ukraine title, Top RBC (April 2, 2010)

- ↑ Ukraine court strips Bandera of Hero of Ukraine title because he wasn't citizen of Ukraine, Gzt.ru (April 3, 2010)

- ↑ Bandera writes to Yanukovych, Kyiv Post (April 9, 2010)

- ↑ The informational agency UNIAN (Ukrainian)

- ↑ Lavrynovych wonders why Yushchenko did not entitle Yaroslaw the Wise. Focus, 2010 (Russian)

- ↑ Kommersant (May 14, 2010) (Russian)

- ↑ Nadvirna city council awards honorary citizen titles to Bandera, Shukhevych, Lenkavsky, Kyiv Post (March 25, 2010)

External links

- Stepan Bandera, His Life and Struggle

- Bandera's supporters ready for new battle (editorial) - Kyiv Post (March 11, 2010)